Defining Your Legacy

With Lebanese cookbook author Maureen Abood.

Hello lovely readers! How are things? Things here are busy, but mostly good. I am tired, so I am tuning in to and respecting that feeling by trying to make choices around how and where I carve out time for rest. I hope that you find moments of ease and restoration in your day. As always, thank you for being here!

LEGACY: a gift by will especially of money or other personal property. Something transmitted by or received from an ancestor or predecessor from the past. (Source: Merriam-Webster)

Legacy is a word that carries a lot of weight for me. Maybe it is its multi-layered meaning, the heady implication of making meaning of one’s life—what it all means, what it’s all for, and what we wish to leave behind. It’s not just how we want to be remembered, but what we hope will carry on and how that takes shape beyond mere memory.

Recipes are an incredible marker of legacy. The most important story I’ve written so far is a personal essay about making my sita’s pita bread for Food52. My Lebanese American grandmother was so important to me—the way that she nourished me, yes, but also the way that her love sustained me long after I’d used her freshly baked pita to swipe the last of the hummus from my plate, long after I’d boarded the airplane that would carry me back to whichever country my family was calling home that year.

By making her pita bread, I felt I was honoring her. But making her bread and writing about the experience of making it, I realized that it was a way to continue carrying forth the legacy of her ancestors too. I remember FaceTiming with my mom after I’d finally succeeded in making the pita—the foundation was Sita’s but the ingredient proportions and the desired puffy-chew texture was all mine. My mom said: “If only they could see. You, carrying on the tradition. They would be so proud and understand what they built in this new land, in this country. They gave up everything and came here with nothing, but they had their traditions. And baking bread was such an important part of it.” Here she paused, blowing her nose, and I knew the tears couldn’t be far behind. “It makes me so proud and so happy because I think that was such a big trauma. Such a thing to pull up stakes and come to this new land and build a new life and raise nine children on my dad’s side, ten on my mom’s side. How proud they’d be that something so solid has been built and passed on from one generation to another. That foundation, they came with their recipes. The staff of life—the bread.”

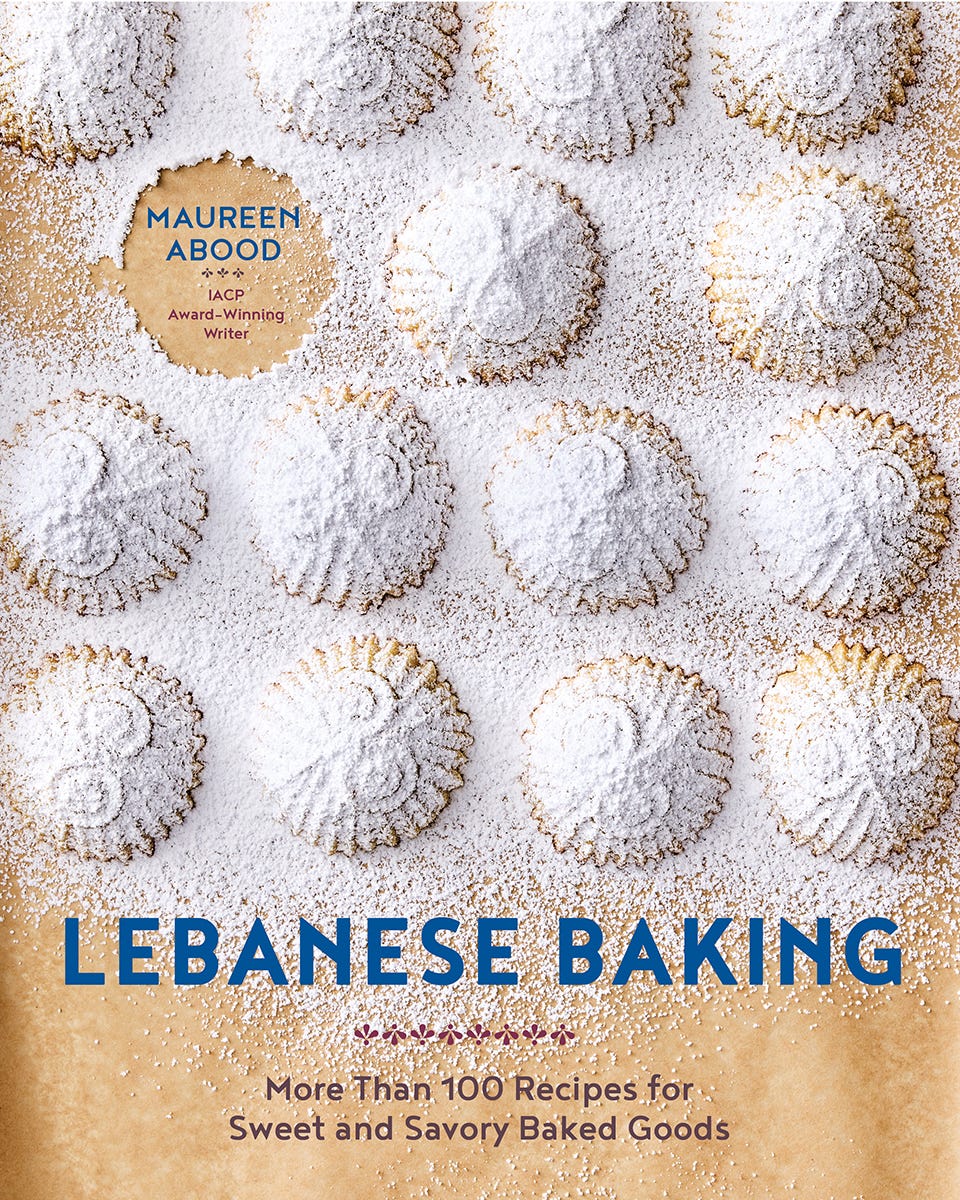

I think this sentiment of baking to connect to my heritage is why I was so taken by cookbook author Maureen Abood’s latest, Lebanese Baking: More Than 100 Recipes for Sweet and Savory Baked Goods (Countryman Press). Abood (pictured above, in a lovely author photo by Stephanie Baker), a second-generation Lebanese American, has devoted her career to Lebanese food—writing about it, developing recipes around it, cooking it, and educating others about it. In Lebanese Baking’s introduction, she writes about how the “book blossomed in the wake of my mother’s death,” and how with that loss came a series of realizations. “Recipes give us access to memories, wisdom, connection. Baking offers beauty in solitude and in community. We continue the conversations with those who baked for us in the past by continuing to bake and by sharing those conversations and traditions with future generations. Baking enacts a rich, braided conversation that never ends.”

One of the seminal recipes in Lebanese Baking is Saj Bread, soft, thin, chewy loaves that Abood’s sitto (grandmother) made and to which Abood attaches strong memories, both past and present. “She would come to our house, spend the night, wake up early, make a giant batch of dough and I would help her with it. It was just fascinating to me to see this dough, to put my hands in this dough. She was one of these very welcoming bakers who wanted the kids around,” Abood told me when we chatted by phone, describing how her sitto loved coming to their house and baking breads in the basement, and how she made all kinds of things from that same dough. Abood followed that same approach for a time, but then realized the nuances for each bake and the outcomes she desired would require different approaches to the dough for the different recipes in her book. “This is where you take and absorb everything you possibly can from everybody you can meet and all the books you can read, and then you depart into your own expertise—this is what I bring to it, is the next level of refinement, streamlining, the rigorous recipe development. In so many ways it’s a book for me, it’s a personal book, it’s a family recipe book, and then it’s so much beyond that as well. Because I used what I loved and learned as a launching pad.”

Lebanese Baking is deeply personal, but it also fills a niche and takes up space in the larger cannon of baking books. “We needed this book on our shelves and in our kitchens in the same way bakers and lovers of culture and food want to learn about various cuisines,” Abood says. “You know, I have my German baking, I have my Scandinavian baking, I have my Italian baking—all these books from different cultures. I really wanted us to have a Lebanese baking book that could be right there next to the others and be as exciting and interesting to pull off the shelf and bake from.”

Part of my sita’s legacy also lies in cookbooks. When she passed, my mom and her sisters set up the Mary Khoury Memorial book collection at the Dickinson County Library in Iron Mountain, Michigan. I had thought we’d included Abood’s first book, Rose Water & Orange Blossoms, but it turns out the library purchased that title on their own. But you can be sure we’ll be purchasing a copy of Lebanese Baking to add to the collection of Lebanese and Middle Eastern cookbooks.

One of Sita’s recipes that I still haven’t felt ready to make is bakalva (also spelled baklawa). Baklava is a dessert that looms large in my memories and my imagination, so maybe it’s the notion that my baking results will never match the nostalgia-suffused bites of my childhood. Sita would make a pan of baklava, cut them into diamond shapes, and nestle each into a pastel-hued muffin liner and pack them in a tin, to be served for dessert with coffee on special occasions and family dinners alike—our family dinners at her table in Iron Mountain always felt like a special occasion, especially the summers when we’d had to travel upwards of 24 hours from Jakarta, Indonesia, to arrive there. Maybe as an adult I’m plagued by a scarcity of time mindset—her baklava recipe feels too much like project cooking, and I want to enjoy the process of brushing melted butter on each delicate layer of phyllo dough, rather than rushing the process just to cross something off my culinary conquests list. And as with her pita bread recipe, I think I am partly paralyzed by the particular fear of failure produced by perfectionism, already anticipating the disappointment if the top layers don’t achieve that crisp, crackly layer that yields to the fragrant, syrupy, ground nut filling within.

But poring over the pages in Lebanese Baking, Abood’s recipe for Baklava Diamonds jumped out at me, sparking a mixture of hope and desire in my heart. As she writes in the recipe’s hednote, she writes, “My fast and easy method for this ultimate classic doesn’t require buttering every layer, and it still comes out just as light and crisp.” She learned the butter-pour-over method from her great aunt Rita, who had to develop efficiencies to accommodate the quantities of baklava she baked for various celebrations, the holidays, and her own burgeoning baklava side hustle in Lansing. “She made so much she was rendering 50 pounds of butter for her holiday baking,” Abood says.

Abood’s modified baklava recipe is a perfect example of how each generation carries forth legacy, putting their own stamp on it and inspiring future generations. In fact, in Lebanese Baking, there’s a whole baklava chapter, including recipes for Baklawa Nests, Cream Baklawa, Baklawa Crinkle, Triple Chocolate Baklawa, and Baklawa Diamonds with Homemade Phyllo dough (depicted in the photos here by Kristin Teig). In speaking with Abood about legacy, recipes and cooking, family and tradition, I realized that legacy isn’t static—its definition evolves with each person, with the passage of time, with a deeper connection to oneself, and the ebb and flow of our communities and personal circles.

“Legacy, for me, is that which has been given and that which we are called to give and share. What rises to the top is going to be different for every person as to which facet of their personal legacy that they’ve been given is going to settle in and take root in their own soul so that they can then cherish it and carry it forward for themselves, for others—their peers, their community, their living circles—and what they are going to do to preserve and share for the future,” she says. “And not everyone thinks about legacy that they’re going to leave. Not everyone thinks about legacy they’ve been given. But in my realm, where it has to do with food and culture and memory, and love, ultimately, it’s like an unending quest because I feel like I continue to discover the legacy that I’ve been given. It’s not a moment in time. It’s not a finite knowing. It’s a rich, ongoing revelation.”

My brother, Anthony, became a chef in part to carry forward our sita’s recipes and traditions. He makes beautiful pans of baklava, often tucking them into elaborate boxes to offer as gifts, for birthdays or holidays or just because. He is planning a visit to see me and my family in Roanoke soon, and I’m already planning to make a tray of Abood’s easy Baklava Diamonds, filled with love, hope, and, I hope, delicious memories and conversations.

Love this so much, especially that your grandmother's cookbook collection is housed in an actual, real library, and other cooks in the community can honor her legacy. Please please please write a post about making baklava with your brother during his visit! Also, today's post reminded me of the poem "Gate A-4" by Naomi Shihab Nye. Do you know it? I tear up every time.